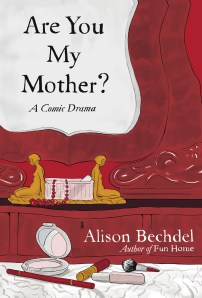

I loved the sneak peek I got of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Are You My Mother? I was intrigued by the complex relationship between Alison and her mother, moreover, I was intrigued by Alison’s mother herself. A voracious reader and amateur stage actor, Alison’s mother had to deal with an unhappy marriage. Alison struggles to reconcile memories of her mother patiently writing down daily journal entries for her with memories of her mother being distant, no longer kissing her goodnight at a young age.

I loved the sneak peek I got of Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Are You My Mother? I was intrigued by the complex relationship between Alison and her mother, moreover, I was intrigued by Alison’s mother herself. A voracious reader and amateur stage actor, Alison’s mother had to deal with an unhappy marriage. Alison struggles to reconcile memories of her mother patiently writing down daily journal entries for her with memories of her mother being distant, no longer kissing her goodnight at a young age.

There are some genuinely touching moments in this book. The nights Alison and her mother spent, for example, writing down detailed accounts of the day in a journal. I also love the parts about Alison’s mother acting, moments of joy that stood in sharp contrast to her weary plea to a young Alison to let her have some private “me time.” The mother’s discomfort with Alison’s homosexuality, and with Alison revealing so much about their private lives in Fun Home struggle with the mother’s reticence in speaking about feelings.

Personally, I would have preferred more scenes of their interaction and a lot less intellectual reflection. This is more a matter of personal preference rather than a commentary on the quality of the book — what the author has set out to do, she does very well. It’s just too detached a treatment for me, and I got bored.

In struggling to understand her relationship with her mother, Bechdel examines the work of psychoanalytic analyst D.W. Winnicott, who studied the relationship between the child and its mother. Bechdel reflects on her relationship with her mother in terms of Winnicott’s work, for example, Winnicott’s play therapy is linked to her own memories of playing with her mother. At one point, she confesses to her therapist that she wishes Winnicott were her mother, which I guess is because she feels Winnicott understands children in a way her mother never did.

Bechdel also writes about Virginia Woolf, particularly about To the Lighthouse, and again, relates her reflections on her relationship with her mother to the Woolf novel. I like how, later on, Bechdel realizes that her mother must have read A Room of One’s Own, and how this is somewhat similar to Bechdel herself being influenced by the words of Adrienne Rich. However, as Bechdel ruminates on To the Lighthouse, I found myself tuning out again. Confession: I also couldn’t stand To the Lighthouse. I know it’s a classic work of literature and full of symbolism and so on, but I found it a boring, frustrating read. Like Woolf, Bechdel’s narrative loops, coming back to the same memories and offering a bit of new insight each time. Also like Woolf, Bechdel examines the tiniest details for significance, and then links it to psychoanalytic theory, or relates it to a dream that she recounts to her therapist. So, if you do like that style, perhaps Bechdel’s endless intellectual ruminations in Mother will also be more to your liking.

Are You My Mother? is a well-written book, and Bechdel’s illustrations are as good as ever. I liked the portrait Bechdel creates of her mother, and their scenes together are touching. I could have done with a lot less of the psychoanalysis and reflections on Woolf and Winnicott, but I can see how other readers may find that fascinating. Overall, well done, but not my kind of thing.

+

Thank you to Thomas Allen Ltd. for a finished copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.