I looked up Cyril Hare’s An English Murder at my local library after seeing it listed in The Guardian as one of the Top 10 Golden Age Detective Novels. I’m always eager to expand my grey cells’ repertoire beyond Agatha Christie (and perhaps even give my inner detective a fighting chance every now and then!), so I decided to give this a go.

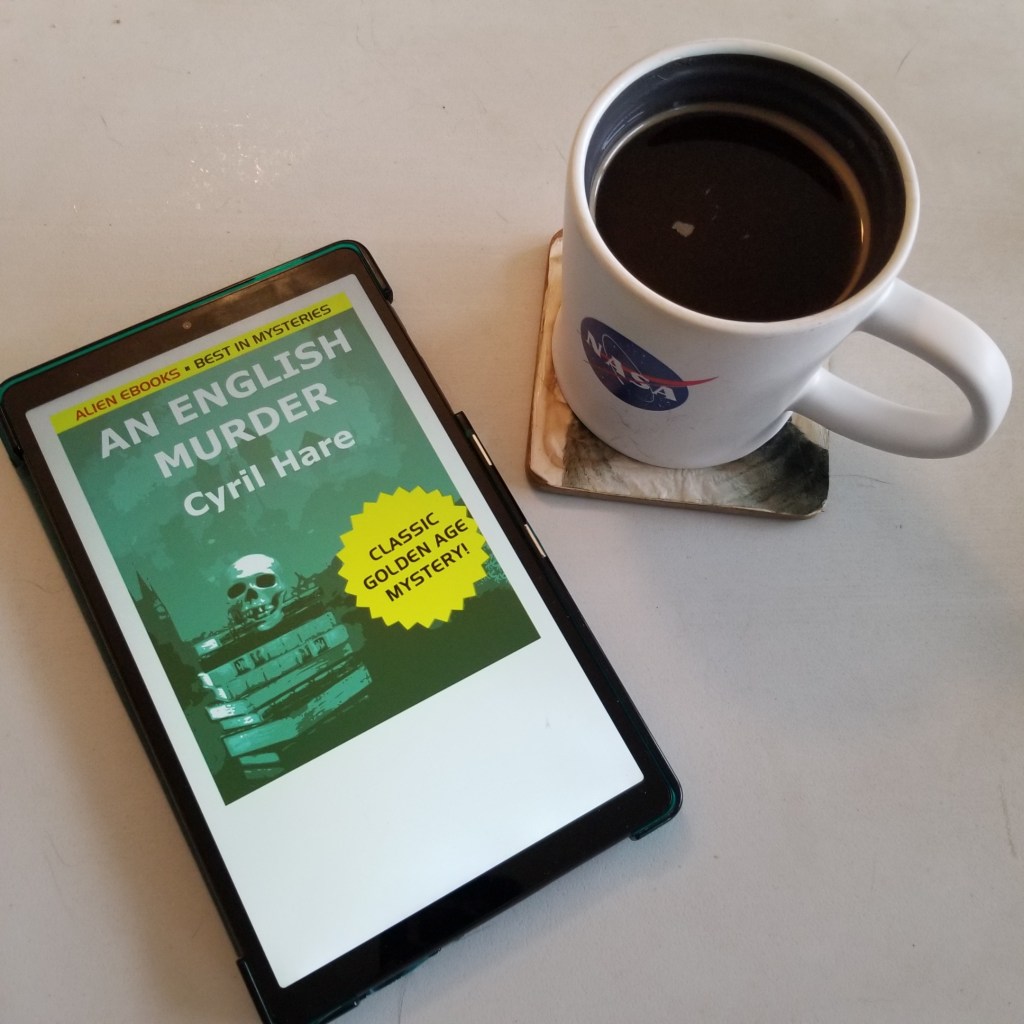

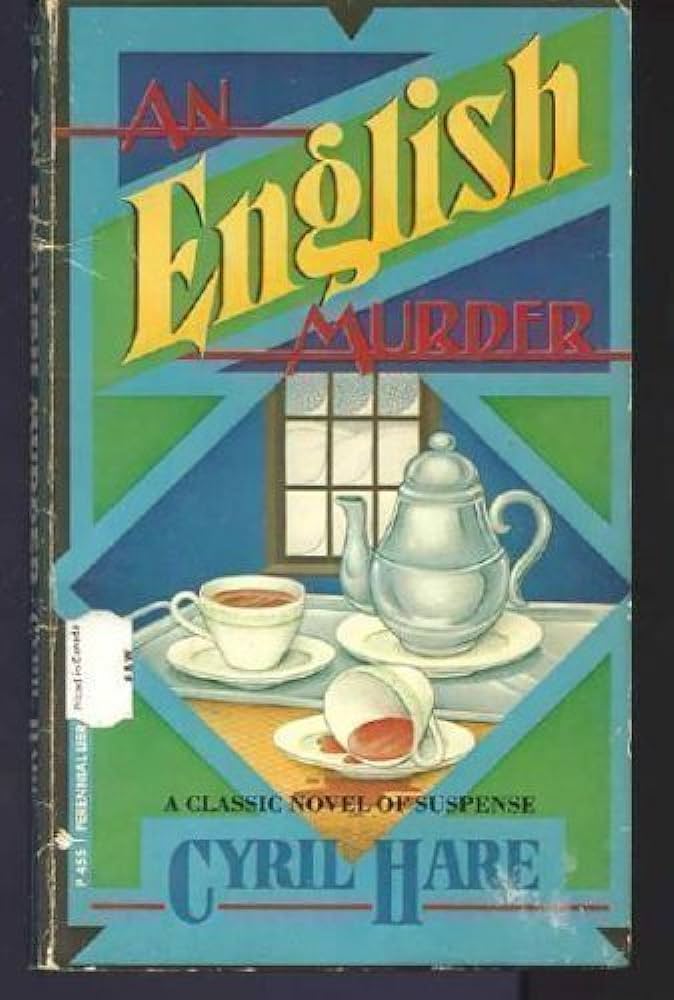

First, I’ll say I was almost turned off by the cover design. Having never read this author before, I was too cheap to purchase a copy with a better one, but just for my own satisfaction, here’s the gorgeous cover of the original 1951 mass market paperback edition:

The set-up is one of my favourites: it’s Christmas at Warbeck Hall, a beautiful and old English country estate, and family and friends have gathered to celebrate the season. On the guest list are: a socialist politician, the leader of a fascist group, an earl’s daughter nursing unrequited love for the fascist, the ambitious wife of a mid-level government worker, and a Jewish history professor and concentration camp survivor who is researching the family’s history. In the servant’s hall are: the family butler, his daughter, and the police officer acting as the politician’s bodyguard. Add in a winter snow storm, a rather juicy secret, and a dying patriarch, and to paraphrase Sherlock Holmes, murder is certainly afoot.

I love how this story touches on the politics and economic realities of post-WWII Britain. Briggs the butler comments on the challenges of putting on a party with such a small household staff. He and his daughter Susan also represent two generations’ approaches to generational wealth, with Briggs being bound by social order and Susan wanting to do away with it. Sir Julius and Robert Warbeck lock horns over competing politics: Sir Julius thinks Robert’s fascism is reprehensible; Robert views Sir Julius’ socialism as being a traitor to their class.

Dr Bottwink’s experiences at a concentration camp are mentioned only in passing, but he isn’t shy to tell Briggs he’d prefer not to eat with Robert. And when Sgt Rogers later comments at how much Dr Bottwink has moved around, the professor corrects him that it’s more accurate to say he was moved, and that this circumstance has turned him leftist — not quite communist, but “anti.” There’s a great moment after the first murder where Dr Bottwink is first to breakfast, and he asks Briggs not to leave the dining room till the next guest arrives. Life experiences have taught him to be cautious: on the off-chance someone dies at this meal, he can’t afford to have been left alone with the food at any time. Neither Briggs, nor Sir Julius who arrives next, both of whom are Englishmen, even realize why that could be a risk.

The mystery itself unfolds at a quick and entertaining pace. Events occur, information is revealed, and tea and champagne are served. I have a feeling that when the big reveal finally unfolds, the killer’s identity and motive will turn out to be so utterly obvious that I’ll hang my head in shame that I didn’t guess it at all.

The thing is, the first murder is easy enough to predict. The victim is someone whom pretty much everyone else at the estate had reason to hate, so when they declare they have a big announcement to make, and then promptly drink a glass of champagne, it’s no big loss when they drop dead. Figuring out whodunnit is trickier, because so many people had motive to.

But then two more deaths follow, and the third death in particular doesn’t fit the pattern at all. Who could have wanted that third person dead? How does their death fit in with the other two?

I have my theories, and none of them make sense. Alas, I’m reaching the 90% mark of the ebook, and things are beginning to wind down. So I’m going to give this a go, and see how I do!

UPDATE: Some significant new clues in the penultimate chapter! I may need to revise my verdict… Now at the start of the final chapter, and it’s now or never to lock my verdict in!

Did I Solve It?

Ahahahahaha! Absolutely not! Not even close! In my defence, the reveal hinged on a bit of history and law that I knew absolutely nothing about, so despite all my research, all my careful note-taking, and all the workings of my poor little grey cells, there is absolutely no way I would have guessed that motive. Honestly, I had to read the final chapter twice over just to make sense of the key information that formed the motive, and by the second time, I was laughing out loud, because never was any of that even on the horizon of my knowledge.

Would British readers be better equipped to solve this case? Would history buffs? Possibly. I’m sure there are many, much smarter readers out there who could try their hand at this and find the solution super obvious. I didn’t, and in a rare occurrence amongst my many detecting failures, I don’t actually feel like I should have been able to put the clues together. Man, this case was wild! And a lot of fun to try and solve, failure or no!

*** SPOILERS BELOW ***