When Nicole Georges visits a psychic for her twenty-third birthday, she finds out that the father she’s always believed to be dead is actually alive. Now, having grown up in a family of secrets and lies, Nicole considers the need to confront her mother about two things: the identity of her father, and the fact that Nicole is gay. The back blurb compares Nicole Georges’ Calling Dr. Laura to Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and while Georges lacks Bechdel’s sly humour, she also doesn’t get bogged down by Bechdel’s philosophizing. The result is a straightforward, rather earnest, heartfelt narrative.

When Nicole Georges visits a psychic for her twenty-third birthday, she finds out that the father she’s always believed to be dead is actually alive. Now, having grown up in a family of secrets and lies, Nicole considers the need to confront her mother about two things: the identity of her father, and the fact that Nicole is gay. The back blurb compares Nicole Georges’ Calling Dr. Laura to Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and while Georges lacks Bechdel’s sly humour, she also doesn’t get bogged down by Bechdel’s philosophizing. The result is a straightforward, rather earnest, heartfelt narrative.

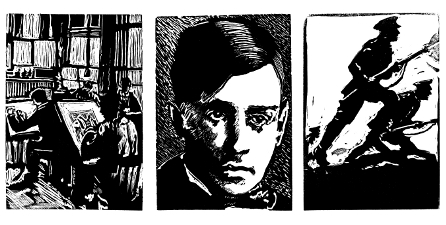

Georges highlights the difference between her adult life and her childhood memories through her drawings — her life in her twenties is sketched with realistic detail, while her flashbacks to her childhood are sketched in simple, stylized shapes such as a child might draw. This shift in style highlights the child Nicole’s innocence, and thereby emphasizes the pain such a figure must undergo, watching her mother being abused by various husbands. I especially love Georges’ use of this technique in a scene where the adult Nicole has a particularly devastating piece of information confirmed, and the character shifts back to the child version for two panels, before shifting back to adult mode.

The Dr. Laura in the title actually plays less of a role in the narrative than I expected. Pressured by her girlfriend to confront her mother, Nicole finally calls Dr. Laura Schlessinger for advice. The author has included bits from the actual transcript of their conversation in the memoir, and while the radio personality seemed harsh, it seemed to be the tough love Nicole needed.

Georges does a good job illustrating the atmosphere of stress and deceit in which she grew up. She relates incidents such as stress-related bowel irregularities that lead to an embarrassing situation with a friend, conspiring with her mother to skip school as long as her stepfather never found out, and having to call 911 when her stepfather tried to strangle her mother. As she later points out, even whens he discovered her biological father was still alive, her experience with fathers hasn’t given her much incentive to find him. She struggles not just with the fear of confronting her mother, which comes hand in hand with her coming out to her mother as well, but also with the fear of meeting her biological father. The simplicity of Georges’ narrative enhances the emotional impact of her decisions; she is thoughtful without becoming too introspective. While her tone felt at times too flippant, it’s an understandable way to cope with her fear, and adds realism to her narrative.

Calling Dr. Laura is a touching tale of growing up, of coming out and of trying to make sense of one’s family. The biggest emotional wallop is reserved for the end of the book. Like the rest of the book, it is heartfelt but rendered with understated precision. It’s telling that Nicole feels most free to talk about her concerns over the phone with a radio personality or over email with loved ones. The medium provides a comfortable layer of protection, yet what comes through most strongly is Nicole’s vulnerability. Calling Dr. Laura is a sweet, simple story, surprising in how much it can reveal through so little. Well done.

+

Thank you to Thomas Allen Ltd for an ARC of this book in exchange for an honest review.