There’s a fantastic scene in the Dungeons and Dragons movie where the druid Doric transforms into multiple animals as she races out of a castle and across a field after a spying mission. Much of the scene is shown through her perspective, so even better than seeing her switch into a mouse or a fly or, later on, a deer, we actually see the world through the eyes of a fly or a mouse or a deer. It’s a fantastic bit of cinematography, and an exhilarating five or so minutes.

There’s a fantastic scene in the Dungeons and Dragons movie where the druid Doric transforms into multiple animals as she races out of a castle and across a field after a spying mission. Much of the scene is shown through her perspective, so even better than seeing her switch into a mouse or a fly or, later on, a deer, we actually see the world through the eyes of a fly or a mouse or a deer. It’s a fantastic bit of cinematography, and an exhilarating five or so minutes.

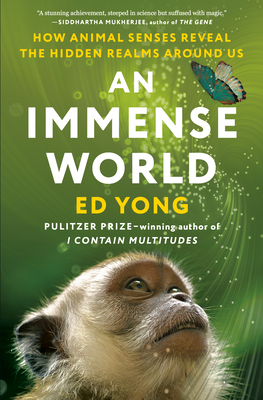

Ed Yong’s book takes us on a similar journey. He shows us how a broad range of animals experience the world, and makes a very deliberate effort to focus on these animals as themselves and not how they relate to humans. He does use human experiences in comparison, to help us understand how each animal experiences sights or smells or touches, but the overall impression is that of being taken through experiences very much alien to us readers. Rather than anthropomorphizing the animals he talks about, Yong invites us to be animorphized into animals (is that the word?).

The result is an incredibly fascinating deep dive into animal life. What must it be like to see in multiple directions at the same time? How must the world seem to someone who can taste with their feet? How much incredibly richer are the scents of the world to a dog than to a human? There’s a particularly cool bit about a kind of insect that has sex near forest fires, and the reason is that the fires chase away this insect’s predators, and so makes the forest safe and food sources easier to access for them and their families.

And on a more sobering note — why are some human actions so harmful to animal life? I’ve heard the stats before of how city lights kill lots of birds every year, but this impact hits different when you read about why darkness is so important for birds when they migrate. In the case of the insect that has sex near forest fires, the smoke from backyard barbecues can mess with their perceptions by making them think there’s a forest nearby that would be a safe place for them to have sex and raise their little insect babies.

The book is chockfull of scientific facts, and as fascinating as it is (my kindle copy is filled with highlighted passages), it does take a bit of time to get through. I also doubt I remember enough to actually answer questions about individual animals I read about. (For example, I think the forest fire sex insects are a kind of beetle, but I wouldn’t be surprised if I got that wrong altogether, as that was from an early chapter and I would’ve read that maybe a month ago.) Still, this is just a good reason to buy a copy of the book for yourself, rather than borrowing it from a library. (I initially borrowed it from the library, but then realized I wanted to highlight so many things that buying my own copy made more sense.) It’s the kind of book I can imagine dipping into over and over again, and honestly, I’m even considering buying a paperback copy so it’s a bit easier to casually flip through whenever I get in the mood.

There are some disturbing bits about the experiments scientists had to do to learn some of these facts. Like, I think these were done on ants? or some other kind of insects? where the scientists removed one or more of their senses to get a better understanding of how these insects navigate the world. That was hard to read, and part of me does feel like the learnings really aren’t worth making the animals suffer like that. But at the same time, I do find the learnings so fascinating that I’m planning to own two copies of this book. And Yong does do a good job of highlighting how conflicted some of scientists themselves are about their actions — a lot of them go into the field of studying animals because they love animals and are fascinated by them. So while I wouldn’t go so far as to say I sympathize with these scientists, I also recognize my own complicity in their actions, and would be hypocritical to blame them.

Overall, I LOVE how this book focuses so much on the animals as themselves. There isn’t much about how this or that understanding of animals’ lives and behaviours are being used to help medicine and planning for humans. Rather, the animals are, and remain, at the center of Yong’s writing, and it is us as humans who take the back seat in this deep dive of their world.